CIRCA in the media

NEIGHBORHOOD REPORT: BROOKLYN UP CLOSE; Class, Brass and 23 Doors

Beulah Smith lived for 44 years in a brownstone at Park Place and Brooklyn

Avenue in Crown Heights. She never took in boarders, and after the death of her

husband, Ivan, she lived alone among the oak paneling, stained glass and flowery

wooden fretwork of her turn-of-the-century house.

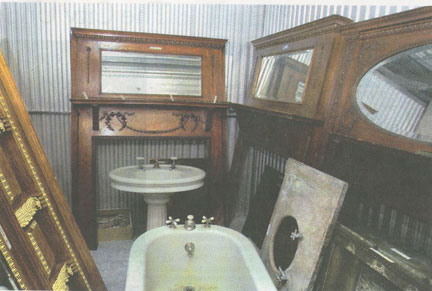

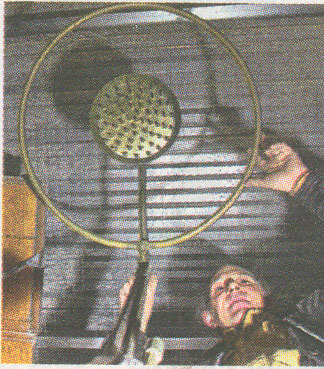

When Ms. Smith died in 1996, at age 94, much of the interior of the house had remained unchanged since 1900. The shower, for example, was a brass affair with a huge dome-shaped spout, suspended above a large, wide-rimmed tub.

Last Thursday, in a self-storage warehouse at Third Avenue and First Street, near the Gowanus Canal, David Goldstein examined that tub with delight. ''It's got these great three-inch rims, which are fantastic,'' he said. ''I'm not crazy about claw feet, and it hasn't got claw feet.''

Mr. Goldstein, a pony tailed former narcotics detective who is now the co-owner of an antiques shop, was taking the measure of an unusual haul; this storage unit and two others contained nearly all the insides of Ms. Smith's home. The tub was surrounded by seven enormous oak mantelpieces; the other units contained stacks of stained-glass window panels, rows of window frames, sinks, wall paneling, Ms. Smith's entire first-floor banister, and 23 doors. ''Doors, doors and doors,'' Mr. Goldstein said, gazing at them affectionately.

Mr. Goldstein and his wife, Rachel Leibowicz, are the owners of Circa Antiques, one of two Atlantic Avenue antiques shops that have bought the contents of Ms. Smith's brownstone. Over six days in late November, workers from Circa Antiques and its partner, Boerum Hill Restoration, gutted the house. They did so at the invitation of its current owner, a drug treatment center called Anchor House that is renovating the building for use as a group home. Anchor House is required to bring the building up to code, a process that it says involves getting rid of almost everything flammable.

At the prospect of carving up the house, ''we were horrified,'' Ms. Leibowicz said. ''This building was in such incredible condition.'' But saving the interior did not appear to be an option. She recalled that a representative of Anchor House had told her: ''If you don't take it out, it's going to be in the Dumpster.'' (The transaction was first reported by Brownstoner, a real estate blog.)

The two antiques shops gave Anchor House a $2,500 donation in exchange for the right to salvage the items, after which Mr. Goldstein and his workers set about gutting the brownstone. ''It was unbelievably hard, dirty work,'' he said. ''We had to have taken out easily 200 pounds' worth of nails. One of my guys said, 'You sure they didn't have nail guns back then?' ''

Items too small or fragile to be kept in the warehouse went to Ms. Leibowicz's store, among them the trove of stuff gathered from behind the medicine cabinet, where it had sat for up to a century. This included murky glass bottles of medicine and a bottle of white shoe polish, from the days when white shoes were de rigueur in summer.

As he surveyed the contents of the warehouse, Mr. Goldstein remarked that

houses in affluent neighborhoods tended not to yield such treasure. ''In the

wealthier neighborhoods, they gutted all this stuff out, because it takes up a

lot of space,'' he said, fingering a foot-deep mantelpiece. But in poorer

neighborhoods, he added, ''this stuff stayed, because they couldn't afford to

remove it.'' ALEX MINDLIN

Photos: Mantelpieces and an ancient tub, above, and, below, David Goldstein examining an old shower head. (Photographs by Angela Jimenez for The New York Times)